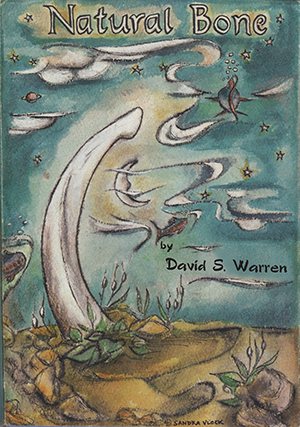

Natural Bone

by David S. Warren

excerpted from Chapter 7 The Hollow Trout In the Natural Bone Hotel

and Chapter 8 (in total ) Professor Peckerstone’s Red Char

Where We Are Now:

Remarkably, no one but its original founder Noah Davey really knew how the village of Natural Bone got its name, and Noah Davey was so old that he should have long since been dead, but still had his store there, although not one of the village residents patronized it and Noah Davy was not a generous source of information. Davy’s store was near the spot where the acid red Oswegatchie River flowed off the granite and ate through the limestone for a ways through a maze of caverns, the main chanel of which popped up in a spring hole not far from the store. The initial section of the caverns could be traveled by a poled boat, and in the past Davy had hired boys to conduct tours for a few people at a time. But no more.

The going businesses of Natural Bone were the talc mine, The Long Horn Saloon, MeKewen’s Barber Shop / Luncheonette, and three Mink Ranches.

Augustus Reader owned the first of the Mink ranches. He was a World War I vet who lost both legs in France and never talked about it. He had a wife who died, and he never talked about her either, or even said her name.

That left him with his daughter Cynthia who stayed home to help, and a son Kurt, who had gone to Korea and managed to return with all his body parts, but with a mind like a jig-saw puzzle dumped in a box. Kurt helped on the Mink Ranch, but without much enthusiasm, and he would wander off into town most every day. He liked to sit in the Long Horn Saloon at the Natural Bone Hotel, drinking the watered beer they gave him, and listening to conversation or talking to himself if there was nobody to listen in on.

Strangers from out of town seldom enterd the Long Horn Saloon, to say nothing about Noah Davey’s vestigial store. But one day the Bus stopped in front of the McKewns Barbershop/Luncheonette, Outside of which Homer Mckewen was asleep in a chair, beside his Saint Bernanrd Benjamin the third who was also asleep, curled up into a large mound unrecogizable as a dog.

Out of the bus a grey woman struggled alone with a small, belted suitcase and a lidded knitting basket in whch Homer would not have been able to see the very small dog shivering there; but Homer and Benjamin the third did not wake up when the bus stopped anyway.

The Hollow Trout In the

Natural Bone Hotel

“You can come out, Minnie,” said Clara to the wicker basket. She put the basket down and opened it. The dog trotted directly under Homer’s chair and peed, scratched and trotted back to Clara.

“Oh God!” cried Clara upon finally seeing the St. Bernard, and she snatched Minnie up.

Quickly, Mrs. Mary McKewen Weir smoothed her blue apron down over her big white dress. She touched the netted bun of her chestnut hair, opened the screen door a crack, and spoke in a very low voice, heard by neither Homer nor Benjamin the Third, “Come on in, dear!

Mary gave her a glass of water and then an ice cream cone. Then she gave Minnie a bowl of water and a tiny dish of ice cream. She made Clara a bacon, lettuce, and tomato sandwich and Clara told her that she and Minnie were looking for a home.

They drank coffee and exchanged life stories. Mary told how she and Homer had come to Natural Bone after Homer (a shoe clerk at the time, studying at barber school nights) had presented her (a pastry cook, come to him for support shoes) with Benjamin the First and a proposal of marriage. They had found Natural Bone on their honeymoon and thought it an ideal place for Benjamin to live and grow, for Homer to start his own barber shop, and for Mary to have her dream luncheonette. So even though Benjamin the First had long ago wandered from his square of cement, swallowed a snake and died in the middle of the street, here they were.

In turn, Clara told Mary how she had left her father and three brothers in Philadelphia five years after her mother had left them. Clara told how she had made a living ever since as a railroad extra gang cook, crossing the country several times in this work, going as far as Alaska, never seeing her mother or family, always looking for a home.

Well, Mary told Clara that she had found it, that she knew just the place for her – the Reader Ranch. So then, without even waking Homer and Benjamin the Third, Clara went off with Minnie and their suitcase, down to the Reader Ranch.

As soon as Clara had left, Mary sat down and wrote out her entire week’s column for the French Lake Weekly Message, then took it outside, she removed the newspaper from Homer’s head and read to him:

“Today Natural Bone gained a citizen. She is Miss Clara Bovrul who, having retired after an exciting career as a wilderness cook, where she was the only woman, had lived for several years in Alaska and California, and has now come to Natural Bone, looking for a home not too near the mountains and not too near the sea, where she can take her part in a family.

“When asked her impression of Natural Bone after having been here only fifteen minutes, Miss Bovrul repled that she thought it was not a very pretty nor a very sensible name, and that it might better be called ‘Middleville’ instead, because it seems like it is in the middle of something.

Miss Borul will be keeping house and cooking at the Reader Ranch just outside of town.”

Mary Weir had been trying to get the name of Natural Bone changed ever since she had moved there, because neither she nor anyone she knew of could give any reason why it might be called by that name. Now, perhaps, she had some outspoken assistance in the cause. However, Mary didn’t send Clara to the Reader Ranch just because she or anyone else needed her there, but also because of the disarming resemblance she bore to the dead Mrs. Reader – a resemblance no one would ever mention to Clara.

_____________________

Cynthia, out in the mink yard, saw Clara come carrying her suitcase and talking to the wicker basket, and she recognized the approaching shade of her own dead mother. For a moment, and many moments afterward, it seemed that Mrs. Reader had never died, but only gone away and then come back after many years, aged only inwardly. Clara had the same habit of placing the back of hand to her forehead and sighing, and she had eyes which glared as much as they melted. So struck by this resemblance that she scarcely heard Clara say she was looking for a home in which to work, Cynthia led her right inside to Augustus who was trying to repair a radio which he had disemboweled on the kitchen table. Equally affected by this strange resemblance and the cold glare with which Clara first took him in, he encircled his radio tubes with his arm and drew them together.

“I’m looking for work and a home for my Minnie and me,” Clara said.

“All right,” was all Augustus said.

He scraped his radio parts off the table into the radio cabinet, took it into the parlor room (which, since shortly after he had added it and a second story onto the house, had been his own room anyway) and shut the door behind him.

Clara Bovrul filled the Reader’s Ranch’s need for a housekeeper and did much more. She did all the cooking; ate only when standing at the stove; and at night when the housework was all done, she baked cookies for Kurt in order to get him to sit beside her on the couch (instead of going down to the Long Horn Saloon where he was, by agreement with the family, given well watered beer) while Clara made doilies after Mary McKewe’s instructions. Clara placed her doilies all around the downstairs.

Augustus Reader had an unmentionable fear of Clara for her resemblance to his dead wife who had also spread doilies around. When he ate at the table and she ate off the stove, he never looked at her or talked to her, though he would refer to her in the third person, as if she were not there. He gave Cynthia money to pass along as house money and wages, but he shut her out of his room, preferring spider webs to her invasive doilies.

That winter Augustus, tied many trout flies and he invented an artificial trout stream.

By spring, Augustus had built the heart of his artificial trout stream on his fly-tying bench. It was a water wheel of tin cans and automobile parts joined on a portable platform to a pump. When the big run-off was over, Augustus and Kurt took the Whippet down to the river and brought back a load of river rocks of all sizes, including the angular boulder with some good moss on it. Then Augustus directed Kurt to wheelbarrow the rocks down the path past the mink yard, through the pine plantation, and to the base of the hill where the spring always gushed out of a pipe in the side of the spring house and fell about three feet into a pool.

Augustus had Kurt dig a new channel for the spring from the pool under the pipe to a point about twenty yards down, but in a dog-leg curve, so that, in its new channel, the water would run nearly twice as far. With the soil from his excavation, Kurt buried a pipe which ran from end to end of the old channel. Augustus directed Kurt to lay all the rocks they had brought from the river in the new stream-bed just where a stream would have put them, with the mossy boulder near the tail of the run.

At the very head, under the falling column of water, they placed the wheel and pump which Augustus had constructed over the winter, and they joined it to the pipe which ran to the lower junction of the old and new channels.

The pump began moving water up from the tail to the head of the run so that, for the new stretch, the flow was doubled. The artificial trout stream kept flowing. The only thing it lacked, of course, was trout. Someday, Augustus said, they would go out and catch a mess of trout to bring back in a milk can; for then he was quite content to have Kurt wheel him down to the stream in the afternoon, or just to wheel himself down, and to dream over the water all afternoon. He hated to strap on the wood and metal legs anymore, and besides, his upper body had strengthened and he could get around better in the chair than with his “damn pegs.” Augustus was so content with his artificial trout stream that he did very little each day after the morning mink feeding, and each evening Kurt had to be sent to bring him up for dinner.

With less household work to do, Cynthia was able to handle more of the ranching responsibilities, though her strongest wish was to let all the mink go. She watched and sketched them as they paced, with fore-quarters only, the fronts of their pens. She hoped for a way out for everyone at the ranch. She hoped and she worked and she waited.

After wheeling Augustus down to the artificial trout stream, would watch the water for a while and then wander toward town. He would end up the Long Horn Saloon, or look over the bridge railing into the river just above the caverns, or sit on the bench in front of Noah Davey’s General Store.

By that time old Noah Davey had so few customers that he was suspicious of any that did appear, and always attempted to frighten off children, loiterers, and strangers.

Whenever Noah came to his store window and, by knocking and bulging his eyes at the window, tried to frighten Kurt away, Kurt only glanced at him and started talking to himself, so Noah finally let him stay on the bench. He was only crazy, and that was okay.

When Kurt had not come for some time to sit on the bench, Noah would even look for him, and when he did come,Noah would come out and give him a candy bar. One day as Kurt sat there talking to himself in two different voices, Noah shuffled back through his long store all the way through to his original, windowless cabin, where he reached into the pocket of an old black coat and pulled out a harmonica.

It was the very harmonica which, many years earlier, Black Jim Worms had found and brought back, when he discovered civilization advancing with iron horses toward Natural Bone, and which Noah had appropriated from him. Noah carried the harmonica out to the bench and handed it without explanation to Kurt. Noah Davey had thin, almost transparent skin devoid of pigment from long years in darknes and one could have seen the capalaries brushing his cheeks and forehead as he turned back into the store, the harmonica was the only gift he had ever made to anyone.

Kurt first, put one end of the harmonica into his mouth as if it were a candy bar, then he stood up, got the harmonica properly across his mouth and walked off, completey absorbed in blowing it. When he returned to the bench only three days later, he played in and out like breathing. He learned so well and so quickly that he gave up talking, not only to others, but to himself as well. So he told no one how he had seen a black ghost, his elbows on his knees and his head in his hands, sitting with him on the bench listening to him play.

Then one evening Kurt came, playing his harmonica, down the path to fetch Augustus for dinner. As he approached, two unmistakable native Brook Trout – an orange flanked male and a less brilliant female – rose from the pebbled bottom of the artificial trout stream and darted about with their heads out of the water until Kurt saw them and stopped playing, and then they sank quickly, becoming indistinguishable from the bottom.

______________________

Augustus and Kurt Reader drove to Robbie Grout’s portable shack to tell him how Kurt’s harmonica had made two trout appear where none had been. Robbie was quick to believe their story and was moved by it to share a secret of his own. He led them to his woodshed and, staying outside himself, told them to go in and look at the fish mounted on the wall.

The fish was strangely high-browed

and glowing trout –– red, blue and black,

with spots like eyes down its flank. Kurt

and Augustus stared for five minutes,

then came back out into the ordinary light.

Robbie told them that he had seen similar fish climbing Crumbled Falls and followed them to a shallow lake where they had gone down a spring hole and under a mountain. He told them how, after years of trying, he managed to raise a few of these fish from under the mountain, and then to catch one, only to have it turn to red powder in the air.

It was a few more years after than he managed to hook another such fish on a live butterfly at the end of a line on a twenty-foot tamarack pole. To prevent the fish from disintegrating like the first one, he dunked it immediately into a bucket of spruce gum which he had kept boiling and on the shore of that shallow lake for two weeks. The pitch-shelled fish seemed so alive and glowed so eerily on Robbie’s wall at night that he was not able to sleep with it there, so he had moved it out to the woodshed. And though he insisted that they not take another of these trout, Robbie agreed that he and Augustus and Kurt might put together one more trip, just to see if they could raise one with the help of Kurt’s harmonica.

Robbie took two weeks to clear a trail wide enough for a wheel chair from Snail Rock, back up to the shallow lake at the foot of the mountain. Back at the mink ranch, Augustus built a twenty-foot rod out of bamboo and ordered a salt water trolling reel to hold a hundred yards of quarter inch nylon rope, and he made up a box of large peacock winged butterflies and swan breasted moths. Each day for a week Augustus wheeled himself out onto the sand flats and practiced with his great rod until he could lay out fifty yards of line and keep it in the air. His arms got so strong in that time that he was able to wheel himself, alone, up the path from the spring, twice a day.

A week or so, the three of them went to Snail Rock and Kurt pushed the wheel chair over Robbie’s trail to the shallow lake where he played the harmonica like an angel raised up a glowing fish at dawn. It reared up and walked across the water on it tail for a full twenty yards under the false butterfly, before it saw them and went back under the mountain. It was just plain magic. They were stunned and you would be too.

When they brought Robbie back his little place, he went to the woodshed and brought them the mounted fish. It was for them to keep.

Augustus hung the fish on his parlor room wall where it kept him awake some nights, and some nights swam burning through his dreams. Then one day while Augustus was back down at his artificial trout stream, Kurt walked up the wheel chair ramp and into Augustus’ private entrance with an empty feed bucket. Kurt left the bucket on Augustus’ work bench, took the fish off the wall and carried it into town to show to Michael Corbin Junior at the Long Horn Saloon and of the Natural Bone Hotel.

Augustus wheeled himself up at dinner time, went up the ramp to his room and immediately noticed that, whereas there had been a fish on the wall, there was now a feed bucket on the bench. In too much of a hurry to put on his legs and drive, Augustus wheeled himself back outside, down the driveway, and right down the middle of the road into town. By the time he arrived at the Long Horn Saloon, the game warden was already there, an argument had broken out among the white-powdered talc miners, the Sheriff had been called, and no one could hear Augustus when he called for someone to help him up the steps and in. The argument got louder and louder and the sheriff came.

“Let me up in there!” Augustus said to him.

“Stand back!” said the sheriff and went in.

To settle the argument which was about whether or not the fish was real, the sheriff permitted the game warden to poke a small hole in its flank with a pencil.

“Poff!” it went like a light bulb.

Suddenly the color went flat;

a scale seemed to form over the eye

and everyone dropped back in surprise.

The sheriff stepped up and examined the hole, he could see that the fish was completely hollow. He invited everyone to see for himself. Some thought that maybe Augustus Reader, who was known to make artificial bugs, had painted the fish on the inside of the shell like someone might assemble a ship in a bottle. Michel Corbin Jr. said that, whether or not is was real, the fish certainly had seem alive before they stuck a pencil into it.

After listening to all this Augustus wheeled off in disgust, unnoticed by anyone else.

Since neither Kurt nor Augustus asked to have the fish back, Corbin kept it on the wall behind the bar of the Long Horn Saloon. Many lies and stories were told about the fish and the stranger who did not even drink came to the Long Horn just to see the hollow trout.

Chapter 8

Professor Peckerstone’s Red Char

The story of the hollow trout in Natural Bone Hotel eventually reached Slade Peckerstone, professor emeritus of ichthyology at Cornell University. He had come to study entomology at Cornell when there were still cowpaths across the quadrangle. On Ezra Cornell’s fallow farm, he netted, sketched, described, coded, and preserved so many specimens so cleverly, that he was chosen to prepare for permanent professorship, held over into graduate school, and allowed to travel on university funds to the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico to follow the annual migration of Monarch Butterflies to a supposed wintering ground, which was, at that time, yet unknown to science.

Just as the steamer, came within sight of the jungly shore, he saw a great descending cloud of butterflies out over the ocean behind the ship. The excited entomologist induced a deck hand to let him down in a life-boat, and he rowed off alone after the cloud of butterflies, which seemed to descend to, and under, the horizon.

He soon lost sight of land and got caught up in a circular current. This great and slow whirlpool brought him repeatedly over a large school of fish which, as he viewed them for the third time, seemed so noble looking that he wept and was converted from entomologist to ichthyologist on the spot.

The fourth time the current brought him over the school of fish, another cloud of monarchs descended over them. Each butterfly flew straight into the mouth of one of these rising fish, and all with no more disturbance than snow falling on water.

In the midst of this silent cloud, Slade Peckerstone stood up, raised an oar and clubbed a surfacing

fish for a specimen. The rest of the fish dove, the monarchs fluttered up and Peckerstone rowed

off with the dead fish under his seat.

Unfortunately for his career, the professor’s fish decayed so rapidly that he was unable to document it very well, and, though he rowed out into the whirlpool every day for the rest of his stay in the Yucatan, he never saw another Red Char, as he had named the fish.

He theorized that they were the extant ancestors of all the New World Char-trout, adapted now to southern seas. He figured then that he could find their spawning grounds, like those of other salmonoids, somewhere in cold, flowing, fresh water. Thought the university continued to sponsor him through his change of fields, and on trips up the coastal rivers of Newfoundland and Labrador, Iceland, and Greenland, he did not find the spawning place of the Red Char, but gained his professorship through a long essay on the olfactory sense of smelts.

One morning when his long fishing expeditions were well behind him, the professor found a baby in a basket on his doorstep. He had never known a woman who might have put it there, but he took it in and named it Charlie. Charlie was raised by a succession of live-in student women who were encouraged to read to him, and he entered Cornell University in philosophy when he was only sixteen and the professor was retiring.

Still, Professor Peckerstone would march up through Cascadilla Gorge to his old office each morning, not because he had any work to do, but because he could sleep there with his head on the empty desk, whereas at home he dreamed each night since retiring that he was pursued by giant red wasps which bore down on him like darkness and death until he woke up with lumps all over his face.

One day the professor walked to his office to sleep and found a newspaper which someone had pushed under his door, featuring a story on a mounted trout in the Natural Bone Hotel. He recognized immediately his long sought Red Char. He went right back home, packed a suitcase, and drove north to Natural Bone without even letting Charlie know where he was going. That evening when a hatch of nearly red Gaddis Flies was rising like mercury up the warming river above the caverns, his black 1949 Dodge pulled off the highway and parked perpendicular to the curb in front of the saloon entrance to Natural Bone Hotel. The car’s red tail lights stuck a foot out into the traffic lane, but there was no other traffic. The professor, wearing a low-crowned and wide-brimmed hat, got out of the car and stood looking back into it. His face, in the shadow of his hat, was so knotted in thought that it looked as if he had been stung by bees. His suit was of some worn shiny material, and it was black too, except for grey suede patches on the elbows and grey, faded armpits. The professor touched his hat, then went to the rear of the car and removed a belted suitcase from the trunk. He walked numbly up the steps to the saloon entrance, leaving the trunk lid up.

The only lights inside were a neon Schlitz sign and a glowing bar clock which indicated four-thirty. Michael Corbin stood behind the bar, an unlit cigarette in his mouth. Corbin lit the cigarette and looked the professor between the eyes, but the professor was looking up at the fish over the mirror.

Its back was blue as water, its flanks were red toward the high brow, shading into blue toward the tail, with spots like eyes and an eye like a cat’s.

Just as the muscles around the professor’s mouth began to twitch, as if he were about to make a remark, there was a loud crash of metal outside.

Michael Corbin ran around the bar, past the professor and out the door. The professor bent down, picked up his suitcase and carried out the door behind Corbin, who stood looking north up the street to where the professor’s Dodge now lay on its back in font of the old gas station. Whatever had hit the car was not in sight. They watched the wheels slowly stop turning. The professor continued staring at the still wheels, but Corbin finally shook his head like a dog with ear mites, frowned at the inverted Dodge, and said to the professor,

“You’d better come in and have a drink.”

“I don’t drink as a rule,” replied the professor, but it was not an ordinary, rule-following kind of day, and he followed Corbin back into the dark saloon.

Corbin went behind the bar and poured the professor a drink from a green, unlabeled bottle. The professor drank it down slowly, but without pause, and he noticed the fish again through the bottom of his glass. He put the glass down and stared at the fish. Corbin filled the glass again, and the professor drank it down again without breaking his stare.

“I’m Professor Slade Peckerstone in Ichthyology,” the professor tried to explain when he had finished his second drink; “I think I’ll need a room.” He was swaying on his stool.

“Glad to meet you,” Corbin responded. “This hasn’t really been a hotel since the railroad left town, but if you don’t mind the dust, I can give you a room and a bed.”

Corbin filled the glass again. The professor nodded and smiled. He drank it slowly down until his eyes had become mere slits, so he didn’t even notice the talc miners who drifted in on their way home and sat down on either side of him, powdered white as ghosts. The miners were talking quietly about nothing much. Wondering why they said nothing about the wreck in front of the old gas station, Corbin went out and took a look. There was nothing there.

Corbin stared for a moment at that empty spot, then took out another cigarette and came back into the bar. He said nothing to the miners about the car, but took the professor’s suitcase and led him up the narrow back stairs. The professor paused on every third or fourth step to sway pleasantly. He slurred finally onto a bed matted with dust, and he slept in his hat,dreaming all night that he floated down a red river through white foam in a big green bottle.

In his dream-rumpled suit, the professor emerged from the Natural Bone Hotel at six o’clock the next morning. He walked without thought of who or where he was, past the abandoned Esso station and then down the old road to Davey’s store at the caverns.

A sign on the screen door said, “Open at nine o’clock only for customers.”

The professor went to the window and looked into the dark store, up and down the aisles of dusty cans, ammunition, and old bread. Suddenly he noticed the old man in grey linen and wide suspenders, a thin goatee and flaring white hair. He knew this man from some dream. The professor tore his eyes from this vision as if he were trying to wake, and he hurried on, thrown into complete distraction. He walked on down to the bridge where there appeared to be a fisherman bent over the railing.

As he drew towards the bridge, the professor slowed and heard what he took to be the musical sound of flowing water,but then he saw a glint of metal as the man on the bridge straightened up and shoved a harmonica into his pocket. The face which then looked up at the professor was like a shadowing cliff.

“Good Morning,” said the professor, “I’m Professor Slade Peckerstone.” In fact he had only just remembered that.

Kurt Reader shoved his hands into his pockets and looked down at his feet. His feet started walking as if disturbed by their owner’s gaze, and Kurt went up the hill to town.

The professor knotted his face and leaned over the bridge railing, looking down into the water so red it stained the rocks. He heard the harmonica again and looked up the road, but the musician was out of sight.

The professor looked at his watch and saw that it was six-twenty. He checked again at six twenty-two, at seven o’clock again, and then stared at his watch from seven-thirty until nearly eight o’clock. In no time it seemed the time had passed, but he could not see the hands move. Again he forgot what he was here for. He looked over the railing and couldn’t see clearly as far as the water. Noise in his head drowned the sound of the river. He thought, “I am dying.”

He went under the bridge and wet his face from the stream and immediately forgot his presentment of death. He looked under stones in the water and found Caddis cases of red sand clinging to the underside of liver colored rocks. He slipped one such rock into his pocket, along with a handful of river moss which he was unable to identify. He climbed up the bank with his samples and walked back up the road.

When the professor reentered the Long Horn Saloon, the Schlitz clock glowed ten o’clock and the morning light was just then reflecting off the polished bar up onto the side of the fish, making it look wet and alive. The professor remembered again why he had come to Natural Bone.

“I want to see the man who caught that fish,” the professor said to Corbin, while looking into the eye of the fish.

“Kurt can take you to him,” said Corbin.

The professor looked down. Until then, he had not noticed that the man he had encountered at the bridge was sitting under the fish, looking into a coffee cup. Kurt looked up at the professor.

“Oh, very good!” said the professor.

Kurt looked back down into his coffee cup. The professor stood, still looking at him for a moment. “Oh,” he said, and sat down. Kurt drained his coffee cup and walked out abruptly.

“When will he take me?” the professor asked Corbin.

“Follow him,” said Corbin. “He’s taking you now.”

The professor hurried out the door and back down the street. He caught up with Kurt just as he started down the hill, and by the time they had crossed the bridge and were starting up the hill on the other side, Kurt had stepped up his pace so much that the professor was falling back. Kurt slowed, but kept twenty yards ahead of the professor all the way to the mink ranch.

They walked past the pens, down the hill in back to the spring house where Kurt stopped and sat down, leaning against the, stone wall and watching Augustus, who sat in the wooden wheel chair with a cigar stub in his mouth, casting his fly over the artificial tout stream. The professor saw how the water wheel which pump to circulate and increase the stream.

The professor finally stepped forward and cleared his throat. “Excuse me,” he said. “I’m Professor Peckerstone. I’m in ichthyology and I’m hoping that you might help me out.”

Augustus dropped his cast on the water and stared at the professor in disbelief. The professor stepped forward and explained how he had long ago discovered a fish similar to that mounted over the bar at the Natural Bone Hotel, off the coast of Mexico. As the professor talked on, hoping by more explanation to get a response, Augustus finally lit his cigar and reeled in his line.

“. . . and so,” said the professor, “I have come to Natural Bone looking for the man who caught the Red Char.”

Augustus chewed on his cigar for a moment. “Okay” he said.

At four-thirty the next morning, the professor woke, went down to the empty Long Horn Saloon, stuffed the green bottle from under the bar and two sticks of beef jerky into his kit bag, then walked to the mink ranch. Augustus Reader was already at the wheel of the Whippet truck. Kurt was sitting in the back, in the wheel chair. The professor put his kit bag in back with Kurt and climbed in beside Augustus.

They drove, rattling like a stove full of bolts, up into the woods and toward the dawning sun. Augustus and the professor bounced in the cab, looking off through the trees in the general direction of the river; Kurt rolled and swayed, playing his harmonica in the wind.

The sun was already up when they pulled alongside the portable shack beside the road. Robbie Grout was already out in his rocking chair. His right leg was crossed over the left, dangling one huge boot; he gazed over the trees across the road.

Augustus picked up his wooden legs by hand and put his feet on the Whippet’s running board, then stepped down and stumped over to Robbie, Robbie took his attention from the sky across the road and rose to meet Augustus.

The professor could not hear what they said, but Augustus turned and pointed to him several times. Then Augustus sat down in the rocking chair and Robbie Grout stepped up onto the foot locker, which was his front porch , and into his shack, to return in a minute with his hat, a pack basket, and a small pump rifle. Robbie put his equipment back with Kurt, then got his rocking chair and put it in the back beside the wheel chair. Robbie rode in the rocking chair beside Kurt, with the rifle in his lap.

They drove on up the highway and then off onto rutted dirt roads. Kurt went through the professor’s kit bag and brought out the green bottle. As they came to a turn-off onto an old logging road full of black raspberry bushes, Augustus saw Kurt drinking from the green bottle, so he stopped, got out, took the bottle from Kurt, and brought it up front for himself and the professor.

The going was much slower from then on and they had to stop at each rocky ford to rest the engine and fill the radiator. At each stop they passed the bottle, but it did not seem to have much less in it than when they started.

They drove into the day, up out of the mists toward Snail Rock, which began to seem to be crawling toward them. They parked finally, right at its granite foot, just as the wind blew three crows across the sky from north to south. Robbie stayed in the rocking chair. So as to arrive at their destination at dawn the next day, they camped at Snail Rock, though there were hours yet before dark.

It seemed to the professor, another dream in which he was stretched out before the fire and saw Robbie Grout stand and climb down from the back of the truck, and Augustus Reader stand up out of the wheel chair. Augustus came close to the professor’s face and asked him a question which he could not hear, but the professor nodded his head and sat up shakily. He was too weak and foggy to walk or talk.

Finally, Kurt helped the professor up and into the wheel chair which had been meant for Augustus. They put a blanket over the professor’s lap and Kurt pushed him behind Robbie and Augustus, who walked ever so slowly over the roots and stones by the light of a pine torch. Kurt put the harmonica all the way into his mouth and played as he walked. The professor fell back asleep and dreamed of nothing at all.

When the professor woke, it was in the dark of a misty morning and he was still in the wheel chair. Fog rolled through the little group which leaned together over him.

“ ‘Bout half an hour,” Augustus said.

Kurt handed Augustus the golf bag which he had been carrying over his shoulder. Augustus removed from it five sections of bamboo and assembled them into a rod with a cork handle as big as a bowling pin and butt section as thick as his wrist. The fog lifted a few feet and the professor could see the lake at their feet.

Augustus carried his completed rod like a flaf pole, and with loops of thick line hanging from his big square hand, he started down the shore. The professor could see the whole lake now, shaped like an eye with the tear duct up between two little mountains. Though his vision was clear, he didn’t feel his own body at all.

Augustus lumbered down the shore to a log jam, where the lake spilled out into a stream. He climbed onto the logs so slowly that he seemed to be nailing his wooden feet to the logs and pulling the nails behind. When he was finally stationed where he had room for a long back-cast down over the outlet, he tied on a white artificial moth nearly as large as a bat, and stood with it held between his fingers, waiting.

Then Robbie Grout picked up a rock bigger than his head and set it a few feet out in the lake. He stepped out onto the rock and squatted there with the butt of the rifle down between his feet.

Kurt waded into the water, sat right down in it, and then, to the surprise of the professor who looked out over a lone lily pad and an unopened lily bud, lay on his back with the harmonica in his mouth.

Then in the east, high up, the professor saw a great pine appear like a tree in the clouds, as the fog dispersed in a mare’s tails. Augustus threw his big white moth into the air and began working the looped line out through his guides, downstream and then up over the lake, down and up, until he had fully fifty yards of line out and the moth was darting around just over the surface of the lake.

The branches of the big pine began to wave in a breeze that brought down three crows out of its branches, glided them over the lake and over the heads of the four men, down the outlet, and out of sight. Kurt drew a long breath through all the reeds of his harmonica and slowly rose to floating; the lily bud began to tremble the surface of the lake rang with tension.

Robbie Grout cocked his rifle. He pulled the trigger. The muzzle flashed and the bullet went unseen into the blue’ the report cracked through the rock and water. The sun came up like a bubble jarred out of a tar pit, burst, and spilled onto the lake; the whole surface quivered with light and music.

In that moment the water became so clear that it could not be seen. There was not even a reflection. And them, darting a foot above the rocks form the other end of the lake, a red and blue shape shadowed the darting moth.

Augustus kept wagging his tree of a rod, sending the moth and fish out to the middle of the lake and back towards the professor many times before he tired and let the line fall behind him.

Robbie stood up on his rock’ Kurt sat up in the water; Augustus leaned forward on his rod and the professor held his breath.

The Red Char swam right up

onto the surface of the water,

walking on its tail almost, and

then came to rest,

balanced perfectly on top

of the lily pad before the professor.

He looked into its eyes. The lily opened, releasing a puff of yellow anther dust. The colors of the fish shifted and changed quickly as the dawn, the grew suddenly brilliant, flashing into he sun like Kurt’s harmonica. The professor’s heart pounded madly, struck by such beauty. He closed his eyes for relief. His face fell into loose folds and his head slumped. The Red Char flipped off the lily pad and darted away back to the other end of the lake and down under the mountain from where it had come.

Robbie Grout stood up on his rock. Kurt reared up out of the water and ran splashing across the lake after the fish. Augustus wedged the butt of his rod down into the log jam, clattered down, and stomped along the shore to the professor.

“What’s the matter?” he said. “Wait a minute. I’ll get Kurt and we’ll get you to a doctor somehow.”

“Oh no,” whispered the professor, “let me stay right here.” But Augustus, wading very slowly over the rocky bottom, floating each foot forward and then pushing it down, did not hear him.

When Augustus was halfway to the middle of the lake, the professor grabbed the wheels of the chair and rolled himself in to the shallow water. He rolled the chair across the bottom and arrived at the middle, up to his wheel hubs, just before August reached the spring hole, in the middle of the lake, the professor removed his hat and set it on his lap. Then from straight above, Robbie’s bullet buzzed through the top of his head, and a cloud of light burst out of his skull. Robbie Grout saw all of this.

When Augustus turned back with Kurt just a few seconds later, he saw the wheelchair in the middle of the lake, but the professor was nowhere to be seen. Augustus got into the wheelchair himself and Kurt pushed him back to the shore where Robbie still stood on his rock.

“Where did he go?” August demanded of Robbie.

Robbie’s mouth was sucked in and sealed tight like a wound that has been healed for a long time. He turned and walked ahead, back toward Snail Rock.

“What happened to him?” August kept calling after Robbie, but each time he called Robbie speeded up and drew further ahead. When August and Kurt arrived back at Snail Rock, Robbie was in the rocking chair in the back of the truck with the gun across his knees. He didn’t speak or look at them, but stared upwards, to where two crows flew from north to south, tumbling in some current high over Snail Rock. Nothing was said.

Nothing would be said later.

There was nothing to say.

They knew nothing.

They didn’t mean to kill anybody

and they didn’t know if they had.

The gun was only supposed to

help the crack of day,

like the music and only magic.